While the Jacobite rebellion in Scotland is even less mentioned in French history than in British history books, the support from France to the Jacobite uprising of 1745 is a fact little known to the British public.

Who were these rebels named the “Jacobites”? The Jacobites were supporters of the Stuart dynasty who fell in the late 17th century and tried to regain power in 18th century Britain. “Jacobite” derives from “Jacobus” in Latin, i.e. “James” in English or “Jacques” in French, James II having been officially the last Stuart king to reign over the kingdom of England1. It was therefore during the “Glorious Revolution” that William of Orange came to power in England in 1688 while king James II went into exile. Interestingly, William of Orange became king of Scotland and Ireland without making an explicit claim. The Jacobite partisans who still believed in the legitimacy of the Stuarts were then mainly concentrated in Scotland, Ireland and England. Many of them had no other choice but to flee into exile to continental Europe following the military defeats of the Jacobite armies against William of Orange in 1688 and 1689, the Hanover dynasty in 1715. 1719, then 1746 at the time when the last Jacobite rebellion ended.

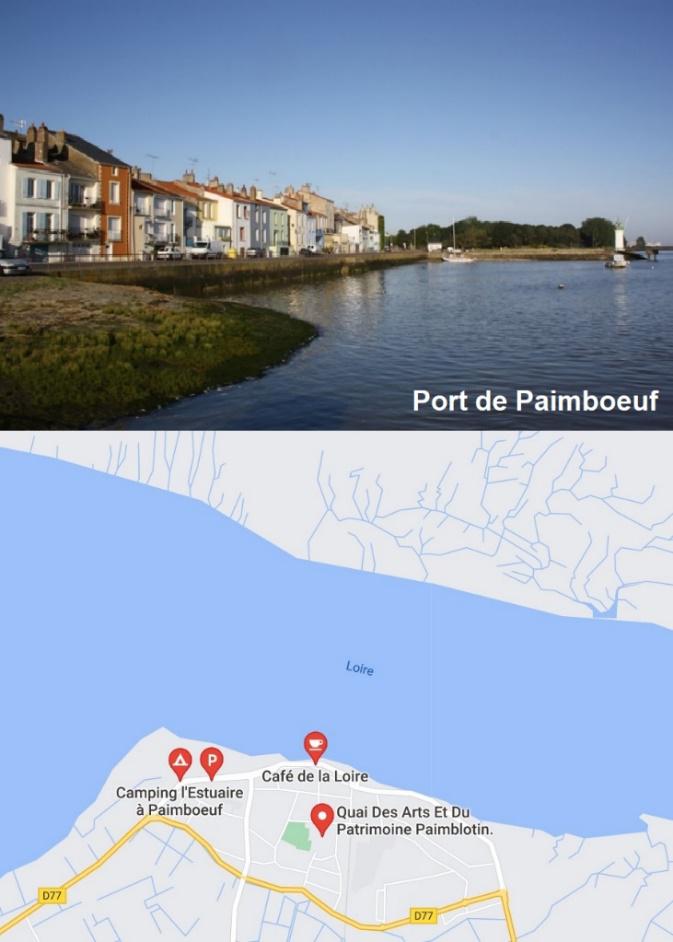

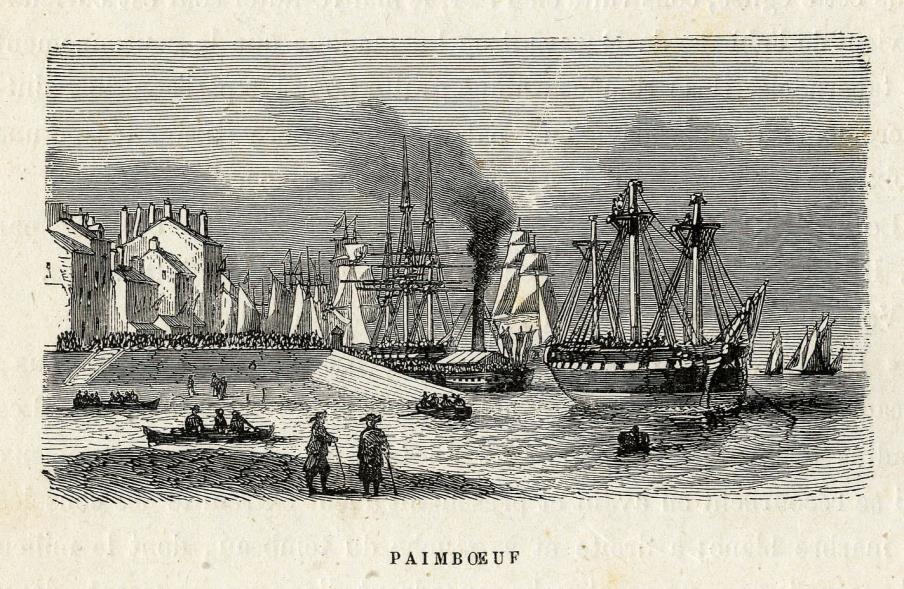

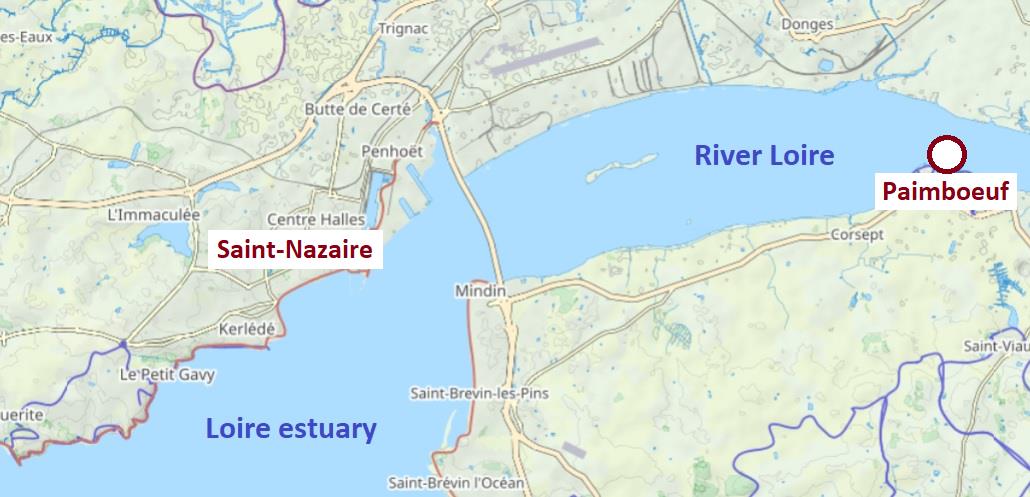

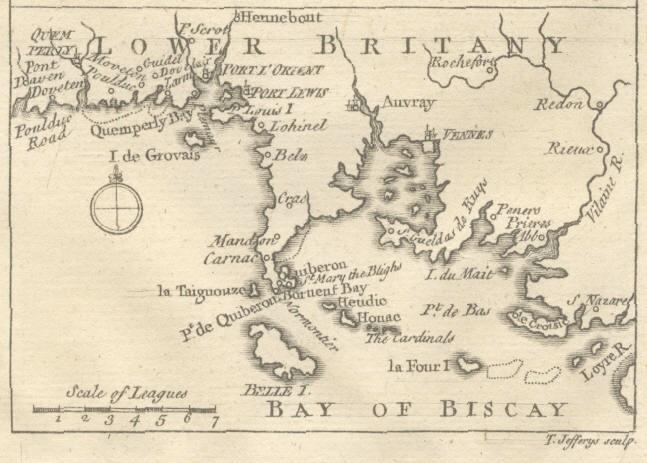

Many Irish Jacobites who were forced into exile following the Treaty of Limerick in 1691 after the defeat of the Boyne (1690) found refuge in many ports in mainland Europe from Spain to the Netherlands, and in particularly in Brittany, given its geographical proximity to Ireland. The Irish exiles settled and prospered in merchant raiding and trade. These settlers of Irish origin, building on their success as privateers, merchants and shipowners, hoped to return to their ancestral land and, with their accumulated wealth, they were able to organize themselves behind Prince Charles Stuart to support his quest for the throne of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1745 and 1746, supplying ships from the Breton ports of Nantes, Brest and Saint-Malo2.

There is now enough information to produce a list of about ten historic sites in Brittany linked to the rebellion of 1745. Visitors from across the Channel will be able to discover and appreciate these sites knowing that they complement the historical context of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 which took place mainly in Scotland and radically changed the history of that nation. Breton sites linked to the Jacobite Revolt of 1745 mainly refer to the maritime aspect of the revolt, a lesser-known part of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. Those sites remind the vital supporting role played by the Jacobites of Irish descent established along the west and north coasts of the kingdom of France. With their wealth acquired in the maritime trade and the sugar cane plantations in Saint Domingue, these Bretons of Irish descent formed a powerful and secret network in support of the Jacobite cause.

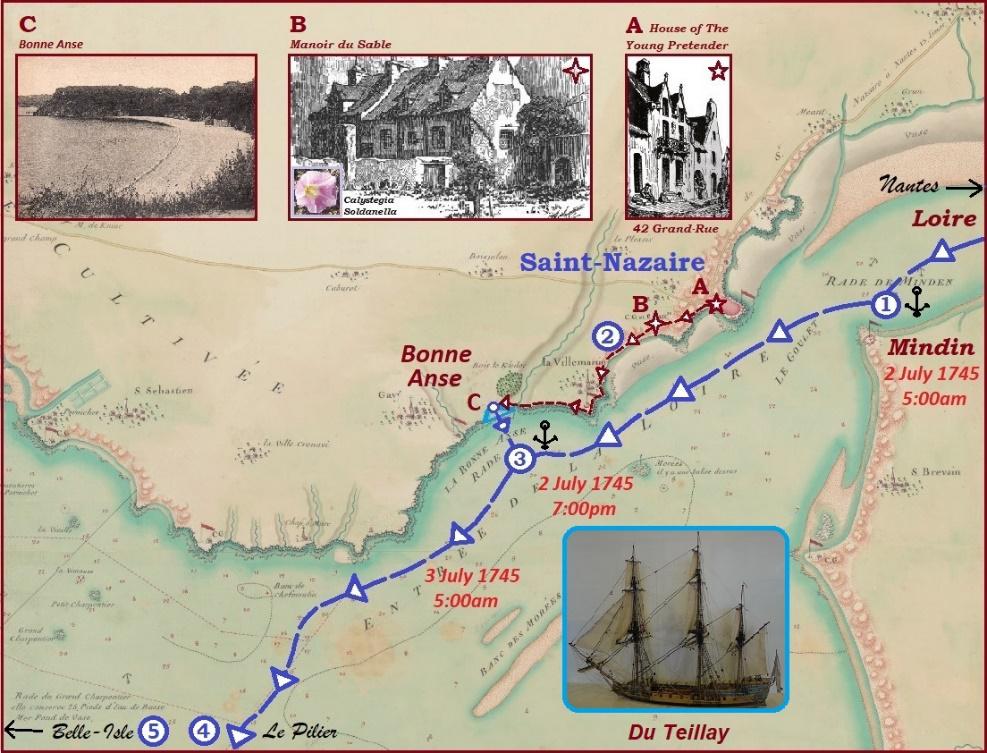

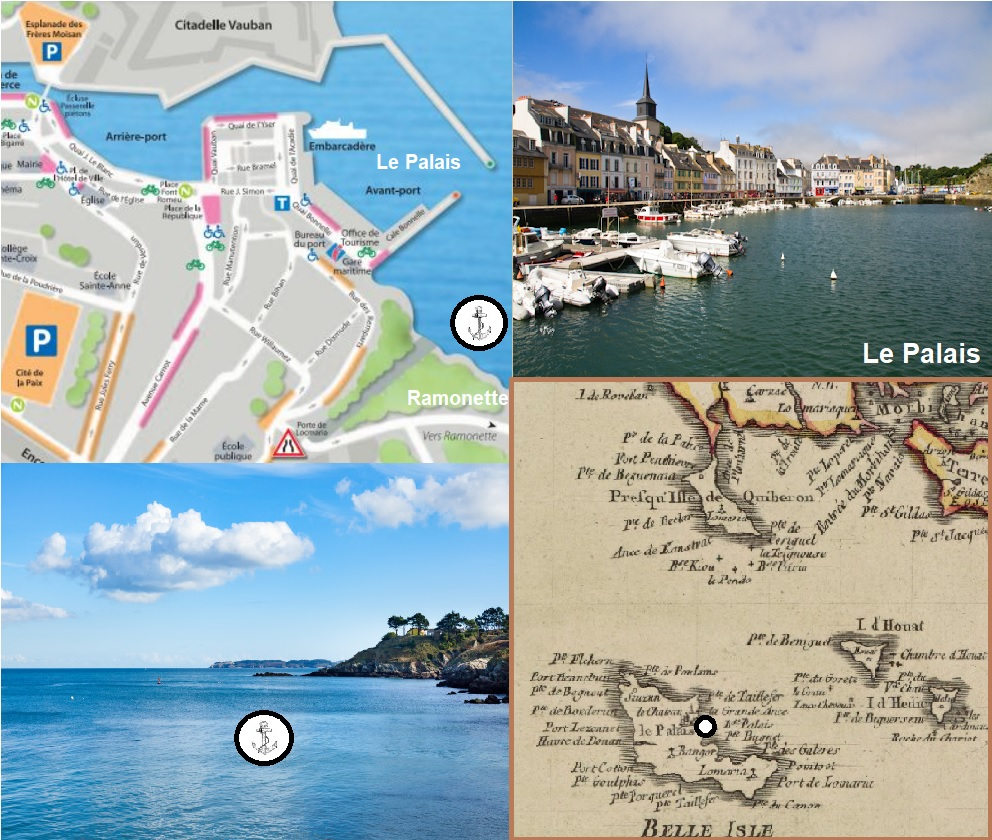

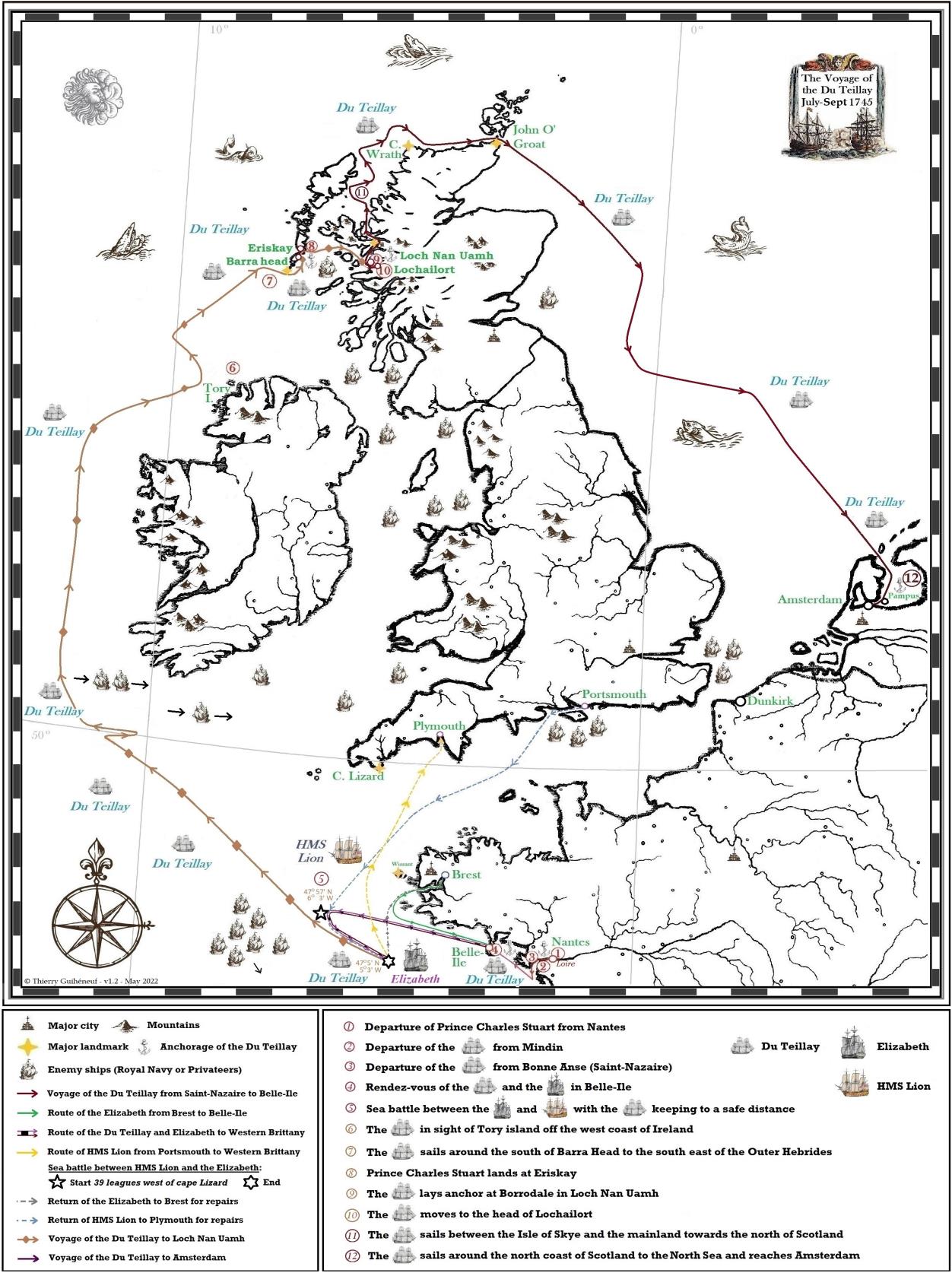

In 1690, the Corsair captain Philip Walsh, an Irish-born sailor and Jacobite supporter settled in Saint-Malo, rescued King James II of England and James VII of Scotland by bringing him back on his ship from Kinsale, Ireland to the safety of the French kingdom. Half a century later, one of Philip's younger sons, Antoine Walsh, was already a staunch Jacobite supporter when he met Prince Charles Edward Stuart in the early spring of 1745. He immediately offered his support for the Prince's quest to reclaim the throne of England, Scotland, and Ireland in the name of his father, James III, known as the “Old Pretender". James III had grown up in the castle of Saint-Germain-En-Laye in the west of Paris before moving to Rome with his family. In June 1745, Antoine Walsh provided Prince Charles Edouard Stuart with one of his ships, the Du Teillay, otherwise known as La Doutelle to travel to Scotland in the upmost secret. Concerned with safety of the Prince, he accompanied him to Scotland in July 1745. After having escorted the young Prince and strengthened by the success of his mission, Antoine Walsh was then charged by Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, count of Maurepas and secretary of the French Navy, to assemble the ships necessary for a naval invasion of Great Britain in November 1745. Later, he organised the supply of gold, powder, muskets, and ammunition, and armed two large frigates of Nantes, Le Mars and La Bellone, for a mission in Scotland in February 1746, this time with the financial support of King Louis XV.

New evidence has now emerged suggesting that one of Antoine Walsh's lieutenants, Antoine Talbot, born in Nantes and aged twenty-eight in 1746, was the same officer who took command of the snaw “Le Prince Charles”, a small three mast ship sailing from Dunkirk to Scotland on February 20, 1746. Captain Talbot was responsible for transporting gold, arms and ammunition to the Jacobite armies in March 1746, three weeks before Culloden's defeat. The ship managed to reach the Kyle of Tongue, in the far north of Scotland, and unload the gold destined for the Jacobite army as he was being chased by a Royal Navy ship, HMS Sheerness. Despite Captain Talbot’s gallant but desperate effort to accomplish his mission, the ship and her crew were captured by the government forces of King George II.

In Saint-Malo, Richard Butler, Antoine Walsh's brother-in-law made his two ships Le Prince de Conti and L'Heureux available to rescue Prince Charles Stuart from Scotland in September 1746. Since April 1746, The Prince had been relentlessly hunted by the governmental forces all over the Highlands and the Outer Hebrides. This rescue mission was organized under the general command of Colonel Richard Augustus Warren, aide-de-camp to Lord George Murray, with the support of Irish volunteers and Breton sailors. Commanding the two privateers were two talented captains of Saint-Malo, the young Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne, aged twenty-two, captain of Le Prince de Conti who was later to explore Tasmania and New Zealand; his elder, Captain Pierre-Bernard Thérouart de Beaulieu, aged thirty-two, commanded L'Heureux, the frigate on board which Prince Charles Stuart embarked from Scotland to land in Roscoff in the north of Brittany where he was given a hero’s welcome.

All these maritime events are a stark reminder of the support provided from the ports of Brittany to the Jacobite cause.

The list of locations hereafter which forms The Jacobite Trail of Brittany are listed in chronological order of the events that took place during the Jacobite uprising from 1745 to 1746. The list is non-exhaustive and new areas of interest will in no doubt can be added subsequently.

[1] He was also the king of Scotland under the name of James VII.

[2] Following the treaty of union between Brittany and France signed in 1532, the duchy of Brittany maintained an autonomy and much of its powers until the French revolution, providing opportunities for the Irish merchants to prosper in Breton ports.